|

|

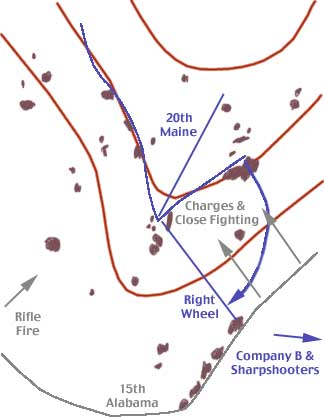

Rocks are in brown, with terrain lines in red-brown. Union in blue, Confederates in Gray |

On July 2nd, the 20th Main held the far left flank of the Union position against the 15th Alabama on the far Confederate right. The traditional account of this fight lauds Colonel Chamberlain for brilliant leadership. While Chamberlain's courage and competence should not be slighted, the following version emphasizes the fog of war, and the role of the individual soldiers.

|

|

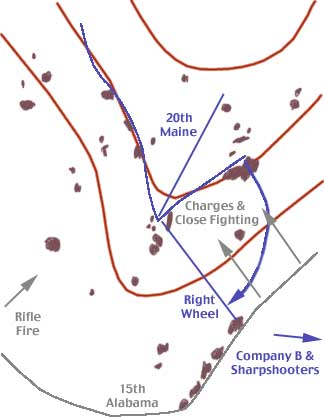

Rocks are in brown, with terrain lines in red-brown. Union in blue, Confederates in Gray |

Vincent's spur is not far from Devil's Den. While the rock formations are not quite as spectacular, there was no lack of hard cover available for both sides, trees as well as rocks. The terrain was also shaped by cattle. The Gettysburg farmers allowed cattle to forage their woodlands. Thus, there was no underbrush, and no leaves on the trees within reach of a cow. While the trees blocked vision high, if one hugged the ground one could sometimes see the feet of one's enemies sooner than anything else.

|

|

Both sides used this cover, and exchanged fire at short range. |

The fight was shaped in large part by two missing regiments. The 47th Alabama started the fight to the left of the 15th Alabama. Their colonel was hit by one of the first volleys from the 20th Maine. The 47th Alabama left the field, leaving a gap to the left of the 15th Alabama. This left the right side of the 20th Main lightly opposed. They suffered far fewer casualties than their left flank, and were able to hold the Confederates at considerable distance.

The other missing regiment was the 16th Michigan. As the 20th went into line, they expected the 16th to be on their left. At last moment, Colonel Vincent shifted the 16th Michigan to his brigade right flank, leaving the 20th unexpectedly holding the extreme left flank. Colonel Chamberlain sent out Company B to act as skirmishers, to go forward, find the enemy, and warn of their approach. As Company B moved forward, the kept shifting to the left, trying to link up with the skirmishers of the 16th Michigan, skirmishers who were not there. In their quest for the missing 16th, they shifted so far left that the 15th Alabama got between Company B and the rest of the 20th Maine.

Chamberlain is sometimes credited for brilliantly dispatching Company B as a reserve flanking force. This was entirely an accident. Company B was a skirmish line that failed to find the enemy, and was isolated from their unit. They linked up with a similarly detached unit of US Sharpshooters, and observed the battle from the distance.

Colonel Oates of the 15th Alabama led from the right side of his regiment. His orders were to find the Union's far left, and turn it. He did so, finding the 20th's left, and sweeping a large portion of his regiment around to hit the unprotected flank. He did not move his troops far enough away from the Union positions, however. By taking positions low to the ground, the northerners were able to see the flanking movement. Chamberlain "refused" his flank, changing his formation from a straight line to a corner. The southerners charged the hill, expecting to turn Chamberlain's flank. Instead, the ran into a well defended line with high ground and good cover. The first Union volley shattered the charge, forcing Oates back. Oates made several subsequent attacks, leading small groups forward, but none of these strikes had the force to break the Union position.

Oates took his time, and better organized one last effort. This last charge bent the Union position back, but at the cost of heavy casualties. Oates lost his brother and best friend within seconds at the peak of the attack, at which point he pulled back. He had had enough. He passed word to his regiment that on the signal, they should run up the big hill.

Chamberlain was equally desperate. His people were nearly out of ammunition. He gave the order to fix bayonets. With the noise and confusion of battle, only a few men heard him, but others followed the example of the first few.

The center company, holding the corner, was desperate for a different reason. One of their men was badly wounded, and had fallen just forward of the main position. The company commander of the center unit requested permission to move forward to recover this man, who was screaming desperately from help. Chamberlain didn't answer this request, saying he was too busy, he was about to order a charge.

|

|

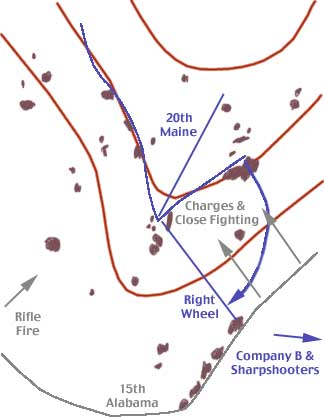

was pushed back by the last Rebel charge, but soon launched a charge of its own. |

It is not precisely clear what happened next. In some accounts, one reads that the formal order for a right wheel forward charge with bayonets fixed was given. Another version has the center company moving forward to pick up its wounded member. The center company had the flag. The soldiers on the left flank, after having fixed their bayonets, responded to the flag moving forward by charging. They 15th Alabama, having been told to run away on the signal, but not being clear what the signal was, may have decided that a bayonet charge might be the signal. On running to the rear, they encountered "two regiments" firing into them. These were Company B (wearing blue) and the US Sharpshooters (wearing green). Neither group was anything near regimental strength, but the Sharpshooters had breech loading rifles. They could fire quite rapidly, providing a sufficient imitation of a regiment to men who had already been ordered to run.

The Alabamans could no loner run north, into the bayonet charge, nor east, into the two suddenly appearing 'regiments.' They then ran west. The bayonet line followed the fleeing Confederates, executing (by accident) a right wheel that had never been ordered, but was what had to be done to maintain the chase. By Chamberlain's account, he never did give the order to charge. However, as his men ran headlong into a mass of surrendering Alabama infantry, he followed his men rapidly enough. The 20th was soon guarding prisoners using empty guns.

The older accounts of the battle emphasizes courage and the competence of the commanders. The newer accounts center on the fog of war, confusion, and the accidents that sometimes turn a battle around. Both accounts are true. The role of the officers, and the men, shouldn't be diminished by the fog and confusion. However, the nature of war is not understood if the desire for glory wipes clean the fog. What happened? At bottom, Oates had decided his best effort had failed, had cost too much, and ordered a retreat. Chamberlain, seeing each attack push further, and out of ammnition, was equally desperate, but ordered an attack. Had Oates retreated before Chamberlain attacked, Chamberlain would have little doubt have been happy to let him go. As it played out, one is left wondering if glory can come by accident.

Next : Devil's Den

The above owes much to former Gettysburg park ranger, Thomas Desjadin, both for his book Stand Firm Ye Boys From Maine, and for a tour of Little Round Top given to the Gettysburg Discussion Group Muster in July of 2000. It is hard to both give full credit to Tom for an excellent book and presentation, and appologize for condensing it so much into a single web page sized byte, and for adding my own spin.